21. Multi-process Sample Application

This chapter describes the example applications for multi-processing that are included in the DPDK.

21.1. Example Applications

21.1.1. Building the Sample Applications

The multi-process example applications are built in the same way as other sample applications, and as documented in the DPDK Getting Started Guide. To build all the example applications:

Set RTE_SDK and go to the example directory:

export RTE_SDK=/path/to/rte_sdk cd ${RTE_SDK}/examples/multi_process

Set the target (a default target will be used if not specified). For example:

export RTE_TARGET=x86_64-native-linuxapp-gccSee the DPDK Getting Started Guide for possible RTE_TARGET values.

Build the applications:

make

Note

If just a specific multi-process application needs to be built, the final make command can be run just in that application’s directory, rather than at the top-level multi-process directory.

21.1.2. Basic Multi-process Example

The examples/simple_mp folder in the DPDK release contains a basic example application to demonstrate how two DPDK processes can work together using queues and memory pools to share information.

21.1.2.1. Running the Application

To run the application, start one copy of the simple_mp binary in one terminal, passing at least two cores in the coremask, as follows:

./build/simple_mp -c 3 -n 4 --proc-type=primary

For the first DPDK process run, the proc-type flag can be omitted or set to auto, since all DPDK processes will default to being a primary instance, meaning they have control over the hugepage shared memory regions. The process should start successfully and display a command prompt as follows:

$ ./build/simple_mp -c 3 -n 4 --proc-type=primary

EAL: coremask set to 3

EAL: Detected lcore 0 on socket 0

EAL: Detected lcore 1 on socket 0

EAL: Detected lcore 2 on socket 0

EAL: Detected lcore 3 on socket 0

...

EAL: Requesting 2 pages of size 1073741824

EAL: Requesting 768 pages of size 2097152

EAL: Ask a virtual area of 0x40000000 bytes

EAL: Virtual area found at 0x7ff200000000 (size = 0x40000000)

...

EAL: check igb_uio module

EAL: check module finished

EAL: Master core 0 is ready (tid=54e41820)

EAL: Core 1 is ready (tid=53b32700)

Starting core 1

simple_mp >

To run the secondary process to communicate with the primary process, again run the same binary setting at least two cores in the coremask:

./build/simple_mp -c C -n 4 --proc-type=secondary

When running a secondary process such as that shown above, the proc-type parameter can again be specified as auto. However, omitting the parameter altogether will cause the process to try and start as a primary rather than secondary process.

Once the process type is specified correctly, the process starts up, displaying largely similar status messages to the primary instance as it initializes. Once again, you will be presented with a command prompt.

Once both processes are running, messages can be sent between them using the send command. At any stage, either process can be terminated using the quit command.

EAL: Master core 10 is ready (tid=b5f89820) EAL: Master core 8 is ready (tid=864a3820)

EAL: Core 11 is ready (tid=84ffe700) EAL: Core 9 is ready (tid=85995700)

Starting core 11 Starting core 9

simple_mp > send hello_secondary simple_mp > core 9: Received 'hello_secondary'

simple_mp > core 11: Received 'hello_primary' simple_mp > send hello_primary

simple_mp > quit simple_mp > quit

Note

If the primary instance is terminated, the secondary instance must also be shut-down and restarted after the primary. This is necessary because the primary instance will clear and reset the shared memory regions on startup, invalidating the secondary process’s pointers. The secondary process can be stopped and restarted without affecting the primary process.

21.1.2.2. How the Application Works

The core of this example application is based on using two queues and a single memory pool in shared memory. These three objects are created at startup by the primary process, since the secondary process cannot create objects in memory as it cannot reserve memory zones, and the secondary process then uses lookup functions to attach to these objects as it starts up.

if (rte_eal_process_type() == RTE_PROC_PRIMARY){

send_ring = rte_ring_create(_PRI_2_SEC, ring_size, SOCKET0, flags);

recv_ring = rte_ring_create(_SEC_2_PRI, ring_size, SOCKET0, flags);

message_pool = rte_mempool_create(_MSG_POOL, pool_size, string_size, pool_cache, priv_data_sz, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, SOCKET0, flags);

} else {

recv_ring = rte_ring_lookup(_PRI_2_SEC);

send_ring = rte_ring_lookup(_SEC_2_PRI);

message_pool = rte_mempool_lookup(_MSG_POOL);

}

Note, however, that the named ring structure used as send_ring in the primary process is the recv_ring in the secondary process.

Once the rings and memory pools are all available in both the primary and secondary processes, the application simply dedicates two threads to sending and receiving messages respectively. The receive thread simply dequeues any messages on the receive ring, prints them, and frees the buffer space used by the messages back to the memory pool. The send thread makes use of the command-prompt library to interactively request user input for messages to send. Once a send command is issued by the user, a buffer is allocated from the memory pool, filled in with the message contents, then enqueued on the appropriate rte_ring.

21.1.3. Symmetric Multi-process Example

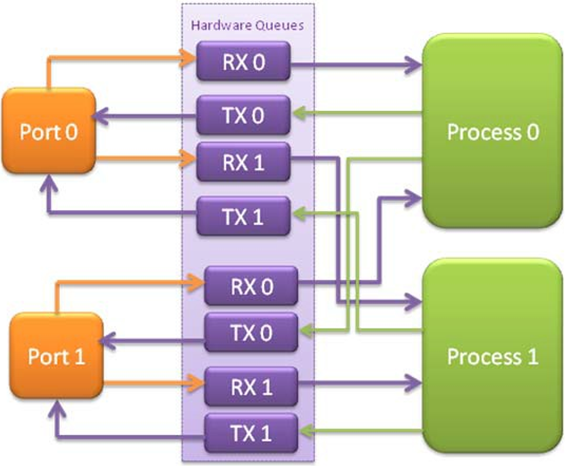

The second example of DPDK multi-process support demonstrates how a set of processes can run in parallel, with each process performing the same set of packet- processing operations. (Since each process is identical in functionality to the others, we refer to this as symmetric multi-processing, to differentiate it from asymmetric multi- processing - such as a client-server mode of operation seen in the next example, where different processes perform different tasks, yet co-operate to form a packet-processing system.) The following diagram shows the data-flow through the application, using two processes.

Fig. 21.1 Example Data Flow in a Symmetric Multi-process Application

As the diagram shows, each process reads packets from each of the network ports in use. RSS is used to distribute incoming packets on each port to different hardware RX queues. Each process reads a different RX queue on each port and so does not contend with any other process for that queue access. Similarly, each process writes outgoing packets to a different TX queue on each port.

21.1.3.1. Running the Application

As with the simple_mp example, the first instance of the symmetric_mp process must be run as the primary instance, though with a number of other application- specific parameters also provided after the EAL arguments. These additional parameters are:

- -p <portmask>, where portmask is a hexadecimal bitmask of what ports on the system are to be used. For example: -p 3 to use ports 0 and 1 only.

- –num-procs <N>, where N is the total number of symmetric_mp instances that will be run side-by-side to perform packet processing. This parameter is used to configure the appropriate number of receive queues on each network port.

- –proc-id <n>, where n is a numeric value in the range 0 <= n < N (number of processes, specified above). This identifies which symmetric_mp instance is being run, so that each process can read a unique receive queue on each network port.

The secondary symmetric_mp instances must also have these parameters specified, and the first two must be the same as those passed to the primary instance, or errors result.

For example, to run a set of four symmetric_mp instances, running on lcores 1-4, all performing level-2 forwarding of packets between ports 0 and 1, the following commands can be used (assuming run as root):

# ./build/symmetric_mp -c 2 -n 4 --proc-type=auto -- -p 3 --num-procs=4 --proc-id=0

# ./build/symmetric_mp -c 4 -n 4 --proc-type=auto -- -p 3 --num-procs=4 --proc-id=1

# ./build/symmetric_mp -c 8 -n 4 --proc-type=auto -- -p 3 --num-procs=4 --proc-id=2

# ./build/symmetric_mp -c 10 -n 4 --proc-type=auto -- -p 3 --num-procs=4 --proc-id=3

Note

In the above example, the process type can be explicitly specified as primary or secondary, rather than auto. When using auto, the first process run creates all the memory structures needed for all processes - irrespective of whether it has a proc-id of 0, 1, 2 or 3.

Note

For the symmetric multi-process example, since all processes work in the same manner, once the hugepage shared memory and the network ports are initialized, it is not necessary to restart all processes if the primary instance dies. Instead, that process can be restarted as a secondary, by explicitly setting the proc-type to secondary on the command line. (All subsequent instances launched will also need this explicitly specified, as auto-detection will detect no primary processes running and therefore attempt to re-initialize shared memory.)

21.1.3.2. How the Application Works

The initialization calls in both the primary and secondary instances are the same for the most part, calling the rte_eal_init(), 1 G and 10 G driver initialization and then rte_eal_pci_probe() functions. Thereafter, the initialization done depends on whether the process is configured as a primary or secondary instance.

In the primary instance, a memory pool is created for the packet mbufs and the network ports to be used are initialized - the number of RX and TX queues per port being determined by the num-procs parameter passed on the command-line. The structures for the initialized network ports are stored in shared memory and therefore will be accessible by the secondary process as it initializes.

if (num_ports & 1)

rte_exit(EXIT_FAILURE, "Application must use an even number of ports\n");

for(i = 0; i < num_ports; i++){

if(proc_type == RTE_PROC_PRIMARY)

if (smp_port_init(ports[i], mp, (uint16_t)num_procs) < 0)

rte_exit(EXIT_FAILURE, "Error initializing ports\n");

}

In the secondary instance, rather than initializing the network ports, the port information exported by the primary process is used, giving the secondary process access to the hardware and software rings for each network port. Similarly, the memory pool of mbufs is accessed by doing a lookup for it by name:

mp = (proc_type == RTE_PROC_SECONDARY) ? rte_mempool_lookup(_SMP_MBUF_POOL) : rte_mempool_create(_SMP_MBUF_POOL, NB_MBUFS, MBUF_SIZE, ... )

Once this initialization is complete, the main loop of each process, both primary and secondary, is exactly the same - each process reads from each port using the queue corresponding to its proc-id parameter, and writes to the corresponding transmit queue on the output port.

21.1.4. Client-Server Multi-process Example

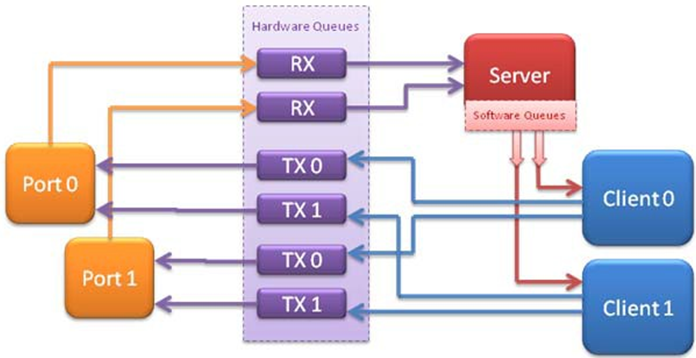

The third example multi-process application included with the DPDK shows how one can use a client-server type multi-process design to do packet processing. In this example, a single server process performs the packet reception from the ports being used and distributes these packets using round-robin ordering among a set of client processes, which perform the actual packet processing. In this case, the client applications just perform level-2 forwarding of packets by sending each packet out on a different network port.

The following diagram shows the data-flow through the application, using two client processes.

Fig. 21.2 Example Data Flow in a Client-Server Symmetric Multi-process Application

21.1.4.1. Running the Application

The server process must be run initially as the primary process to set up all memory structures for use by the clients. In addition to the EAL parameters, the application- specific parameters are:

- -p <portmask >, where portmask is a hexadecimal bitmask of what ports on the system are to be used. For example: -p 3 to use ports 0 and 1 only.

- -n <num-clients>, where the num-clients parameter is the number of client processes that will process the packets received by the server application.

Note

In the server process, a single thread, the master thread, that is, the lowest numbered lcore in the coremask, performs all packet I/O. If a coremask is specified with more than a single lcore bit set in it, an additional lcore will be used for a thread to periodically print packet count statistics.

Since the server application stores configuration data in shared memory, including the network ports to be used, the only application parameter needed by a client process is its client instance ID. Therefore, to run a server application on lcore 1 (with lcore 2 printing statistics) along with two client processes running on lcores 3 and 4, the following commands could be used:

# ./mp_server/build/mp_server -c 6 -n 4 -- -p 3 -n 2

# ./mp_client/build/mp_client -c 8 -n 4 --proc-type=auto -- -n 0

# ./mp_client/build/mp_client -c 10 -n 4 --proc-type=auto -- -n 1

Note

If the server application dies and needs to be restarted, all client applications also need to be restarted, as there is no support in the server application for it to run as a secondary process. Any client processes that need restarting can be restarted without affecting the server process.

21.1.4.2. How the Application Works

The server process performs the network port and data structure initialization much as the symmetric multi-process application does when run as primary. One additional enhancement in this sample application is that the server process stores its port configuration data in a memory zone in hugepage shared memory. This eliminates the need for the client processes to have the portmask parameter passed into them on the command line, as is done for the symmetric multi-process application, and therefore eliminates mismatched parameters as a potential source of errors.

In the same way that the server process is designed to be run as a primary process instance only, the client processes are designed to be run as secondary instances only. They have no code to attempt to create shared memory objects. Instead, handles to all needed rings and memory pools are obtained via calls to rte_ring_lookup() and rte_mempool_lookup(). The network ports for use by the processes are obtained by loading the network port drivers and probing the PCI bus, which will, as in the symmetric multi-process example, automatically get access to the network ports using the settings already configured by the primary/server process.

Once all applications are initialized, the server operates by reading packets from each network port in turn and distributing those packets to the client queues (software rings, one for each client process) in round-robin order. On the client side, the packets are read from the rings in as big of bursts as possible, then routed out to a different network port. The routing used is very simple. All packets received on the first NIC port are transmitted back out on the second port and vice versa. Similarly, packets are routed between the 3rd and 4th network ports and so on. The sending of packets is done by writing the packets directly to the network ports; they are not transferred back via the server process.

In both the server and the client processes, outgoing packets are buffered before being sent, so as to allow the sending of multiple packets in a single burst to improve efficiency. For example, the client process will buffer packets to send, until either the buffer is full or until we receive no further packets from the server.

21.1.5. Master-slave Multi-process Example

The fourth example of DPDK multi-process support demonstrates a master-slave model that provide the capability of application recovery if a slave process crashes or meets unexpected conditions. In addition, it also demonstrates the floating process, which can run among different cores in contrast to the traditional way of binding a process/thread to a specific CPU core, using the local cache mechanism of mempool structures.

This application performs the same functionality as the L2 Forwarding sample application, therefore this chapter does not cover that part but describes functionality that is introduced in this multi-process example only. Please refer to Chapter 9, “L2 Forwarding Sample Application (in Real and Virtualized Environments)” for more information.

Unlike previous examples where all processes are started from the command line with input arguments, in this example, only one process is spawned from the command line and that process creates other processes. The following section describes this in more detail.

21.1.5.1. Master-slave Process Models

The process spawned from the command line is called the master process in this document. A process created by the master is called a slave process. The application has only one master process, but could have multiple slave processes.

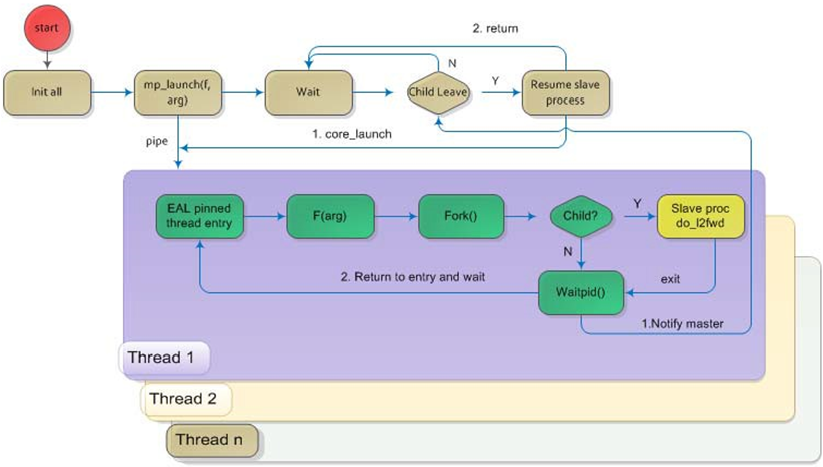

Once the master process begins to run, it tries to initialize all the resources such as memory, CPU cores, driver, ports, and so on, as the other examples do. Thereafter, it creates slave processes, as shown in the following figure.

Fig. 21.3 Master-slave Process Workflow

The master process calls the rte_eal_mp_remote_launch() EAL function to launch an application function for each pinned thread through the pipe. Then, it waits to check if any slave processes have exited. If so, the process tries to re-initialize the resources that belong to that slave and launch them in the pinned thread entry again. The following section describes the recovery procedures in more detail.

For each pinned thread in EAL, after reading any data from the pipe, it tries to call the function that the application specified. In this master specified function, a fork() call creates a slave process that performs the L2 forwarding task. Then, the function waits until the slave exits, is killed or crashes. Thereafter, it notifies the master of this event and returns. Finally, the EAL pinned thread waits until the new function is launched.

After discussing the master-slave model, it is necessary to mention another issue, global and static variables.

For multiple-thread cases, all global and static variables have only one copy and they can be accessed by any thread if applicable. So, they can be used to sync or share data among threads.

In the previous examples, each process has separate global and static variables in memory and are independent of each other. If it is necessary to share the knowledge, some communication mechanism should be deployed, such as, memzone, ring, shared memory, and so on. The global or static variables are not a valid approach to share data among processes. For variables in this example, on the one hand, the slave process inherits all the knowledge of these variables after being created by the master. On the other hand, other processes cannot know if one or more processes modifies them after slave creation since that is the nature of a multiple process address space. But this does not mean that these variables cannot be used to share or sync data; it depends on the use case. The following are the possible use cases:

- The master process starts and initializes a variable and it will never be changed after slave processes created. This case is OK.

- After the slave processes are created, the master or slave cores need to change a variable, but other processes do not need to know the change. This case is also OK.

- After the slave processes are created, the master or a slave needs to change a variable. In the meantime, one or more other process needs to be aware of the change. In this case, global and static variables cannot be used to share knowledge. Another communication mechanism is needed. A simple approach without lock protection can be a heap buffer allocated by rte_malloc or mem zone.

21.1.5.2. Slave Process Recovery Mechanism

Before talking about the recovery mechanism, it is necessary to know what is needed before a new slave instance can run if a previous one exited.

When a slave process exits, the system returns all the resources allocated for this process automatically. However, this does not include the resources that were allocated by the DPDK. All the hardware resources are shared among the processes, which include memzone, mempool, ring, a heap buffer allocated by the rte_malloc library, and so on. If the new instance runs and the allocated resource is not returned, either resource allocation failed or the hardware resource is lost forever.

When a slave process runs, it may have dependencies on other processes. They could have execution sequence orders; they could share the ring to communicate; they could share the same port for reception and forwarding; they could use lock structures to do exclusive access in some critical path. What happens to the dependent process(es) if the peer leaves? The consequence are varied since the dependency cases are complex. It depends on what the processed had shared. However, it is necessary to notify the peer(s) if one slave exited. Then, the peer(s) will be aware of that and wait until the new instance begins to run.

Therefore, to provide the capability to resume the new slave instance if the previous one exited, it is necessary to provide several mechanisms:

- Keep a resource list for each slave process. Before a slave process run, the master should prepare a resource list. After it exits, the master could either delete the allocated resources and create new ones, or re-initialize those for use by the new instance.

- Set up a notification mechanism for slave process exit cases. After the specific slave leaves, the master should be notified and then help to create a new instance. This mechanism is provided in Section 15.1.5.1, “Master-slave Process Models”.

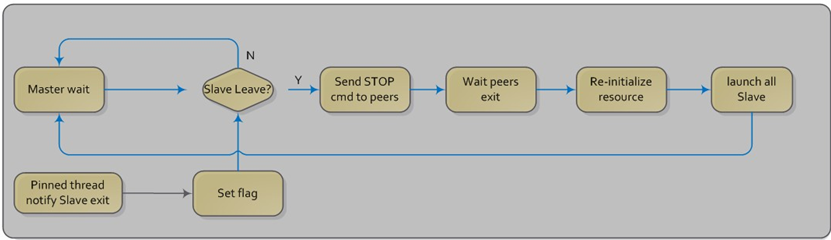

- Use a synchronization mechanism among dependent processes. The master should have the capability to stop or kill slave processes that have a dependency on the one that has exited. Then, after the new instance of exited slave process begins to run, the dependency ones could resume or run from the start. The example sends a STOP command to slave processes dependent on the exited one, then they will exit. Thereafter, the master creates new instances for the exited slave processes.

The following diagram describes slave process recovery.

Fig. 21.4 Slave Process Recovery Process Flow

21.1.5.3. Floating Process Support

When the DPDK application runs, there is always a -c option passed in to indicate the cores that are enabled. Then, the DPDK creates a thread for each enabled core. By doing so, it creates a 1:1 mapping between the enabled core and each thread. The enabled core always has an ID, therefore, each thread has a unique core ID in the DPDK execution environment. With the ID, each thread can easily access the structures or resources exclusively belonging to it without using function parameter passing. It can easily use the rte_lcore_id() function to get the value in every function that is called.

For threads/processes not created in that way, either pinned to a core or not, they will not own a unique ID and the rte_lcore_id() function will not work in the correct way. However, sometimes these threads/processes still need the unique ID mechanism to do easy access on structures or resources. For example, the DPDK mempool library provides a local cache mechanism (refer to DPDK Programmer’s Guide , Section 6.4, “Local Cache”) for fast element allocation and freeing. If using a non-unique ID or a fake one, a race condition occurs if two or more threads/ processes with the same core ID try to use the local cache.

Therefore, unused core IDs from the passing of parameters with the -c option are used to organize the core ID allocation array. Once the floating process is spawned, it tries to allocate a unique core ID from the array and release it on exit.

A natural way to spawn a floating process is to use the fork() function and allocate a unique core ID from the unused core ID array. However, it is necessary to write new code to provide a notification mechanism for slave exit and make sure the process recovery mechanism can work with it.

To avoid producing redundant code, the Master-Slave process model is still used to spawn floating processes, then cancel the affinity to specific cores. Besides that, clear the core ID assigned to the DPDK spawning a thread that has a 1:1 mapping with the core mask. Thereafter, get a new core ID from the unused core ID allocation array.

21.1.5.4. Run the Application

This example has a command line similar to the L2 Forwarding sample application with a few differences.

To run the application, start one copy of the l2fwd_fork binary in one terminal. Unlike the L2 Forwarding example, this example requires at least three cores since the master process will wait and be accountable for slave process recovery. The command is as follows:

#./build/l2fwd_fork -c 1c -n 4 -- -p 3 -f

This example provides another -f option to specify the use of floating process. If not specified, the example will use a pinned process to perform the L2 forwarding task.

To verify the recovery mechanism, proceed as follows: First, check the PID of the slave processes:

#ps -fe | grep l2fwd_fork

root 5136 4843 29 11:11 pts/1 00:00:05 ./build/l2fwd_fork

root 5145 5136 98 11:11 pts/1 00:00:11 ./build/l2fwd_fork

root 5146 5136 98 11:11 pts/1 00:00:11 ./build/l2fwd_fork

Then, kill one of the slaves:

#kill -9 5145

After 1 or 2 seconds, check whether the slave has resumed:

#ps -fe | grep l2fwd_fork

root 5136 4843 3 11:11 pts/1 00:00:06 ./build/l2fwd_fork

root 5247 5136 99 11:14 pts/1 00:00:01 ./build/l2fwd_fork

root 5248 5136 99 11:14 pts/1 00:00:01 ./build/l2fwd_fork

It can also monitor the traffic generator statics to see whether slave processes have resumed.

21.1.5.5. Explanation

As described in previous sections, not all global and static variables need to change to be accessible in multiple processes; it depends on how they are used. In this example, the statics info on packets dropped/forwarded/received count needs to be updated by the slave process, and the master needs to see the update and print them out. So, it needs to allocate a heap buffer using rte_zmalloc. In addition, if the -f option is specified, an array is needed to store the allocated core ID for the floating process so that the master can return it after a slave has exited accidentally.

static int

l2fwd_malloc_shared_struct(void)

{

port_statistics = rte_zmalloc("port_stat", sizeof(struct l2fwd_port_statistics) * RTE_MAX_ETHPORTS, 0);

if (port_statistics == NULL)

return -1;

/* allocate mapping_id array */

if (float_proc) {

int i;

mapping_id = rte_malloc("mapping_id", sizeof(unsigned) * RTE_MAX_LCORE, 0);

if (mapping_id == NULL)

return -1;

for (i = 0 ;i < RTE_MAX_LCORE; i++)

mapping_id[i] = INVALID_MAPPING_ID;

}

return 0;

}

For each slave process, packets are received from one port and forwarded to another port that another slave is operating on. If the other slave exits accidentally, the port it is operating on may not work normally, so the first slave cannot forward packets to that port. There is a dependency on the port in this case. So, the master should recognize the dependency. The following is the code to detect this dependency:

for (portid = 0; portid < nb_ports; portid++) {

/* skip ports that are not enabled */

if ((l2fwd_enabled_port_mask & (1 << portid)) == 0)

continue;

/* Find pair ports' lcores */

find_lcore = find_pair_lcore = 0;

pair_port = l2fwd_dst_ports[portid];

for (i = 0; i < RTE_MAX_LCORE; i++) {

if (!rte_lcore_is_enabled(i))

continue;

for (j = 0; j < lcore_queue_conf[i].n_rx_port;j++) {

if (lcore_queue_conf[i].rx_port_list[j] == portid) {

lcore = i;

find_lcore = 1;

break;

}

if (lcore_queue_conf[i].rx_port_list[j] == pair_port) {

pair_lcore = i;

find_pair_lcore = 1;

break;

}

}

if (find_lcore && find_pair_lcore)

break;

}

if (!find_lcore || !find_pair_lcore)

rte_exit(EXIT_FAILURE, "Not find port=%d pair\\n", portid);

printf("lcore %u and %u paired\\n", lcore, pair_lcore);

lcore_resource[lcore].pair_id = pair_lcore;

lcore_resource[pair_lcore].pair_id = lcore;

}

Before launching the slave process, it is necessary to set up the communication channel between the master and slave so that the master can notify the slave if its peer process with the dependency exited. In addition, the master needs to register a callback function in the case where a specific slave exited.

for (i = 0; i < RTE_MAX_LCORE; i++) {

if (lcore_resource[i].enabled) {

/* Create ring for master and slave communication */

ret = create_ms_ring(i);

if (ret != 0)

rte_exit(EXIT_FAILURE, "Create ring for lcore=%u failed",i);

if (flib_register_slave_exit_notify(i,slave_exit_cb) != 0)

rte_exit(EXIT_FAILURE, "Register master_trace_slave_exit failed");

}

}

After launching the slave process, the master waits and prints out the port statics periodically. If an event indicating that a slave process exited is detected, it sends the STOP command to the peer and waits until it has also exited. Then, it tries to clean up the execution environment and prepare new resources. Finally, the new slave instance is launched.

while (1) {

sleep(1);

cur_tsc = rte_rdtsc();

diff_tsc = cur_tsc - prev_tsc;

/* if timer is enabled */

if (timer_period > 0) {

/* advance the timer */

timer_tsc += diff_tsc;

/* if timer has reached its timeout */

if (unlikely(timer_tsc >= (uint64_t) timer_period)) {

print_stats();

/* reset the timer */

timer_tsc = 0;

}

}

prev_tsc = cur_tsc;

/* Check any slave need restart or recreate */

rte_spinlock_lock(&res_lock);

for (i = 0; i < RTE_MAX_LCORE; i++) {

struct lcore_resource_struct *res = &lcore_resource[i];

struct lcore_resource_struct *pair = &lcore_resource[res->pair_id];

/* If find slave exited, try to reset pair */

if (res->enabled && res->flags && pair->enabled) {

if (!pair->flags) {

master_sendcmd_with_ack(pair->lcore_id, CMD_STOP);

rte_spinlock_unlock(&res_lock);

sleep(1);

rte_spinlock_lock(&res_lock);

if (pair->flags)

continue;

}

if (reset_pair(res->lcore_id, pair->lcore_id) != 0)

rte_exit(EXIT_FAILURE, "failed to reset slave");

res->flags = 0;

pair->flags = 0;

}

}

rte_spinlock_unlock(&res_lock);

}

When the slave process is spawned and starts to run, it checks whether the floating process option is applied. If so, it clears the affinity to a specific core and also sets the unique core ID to 0. Then, it tries to allocate a new core ID. Since the core ID has changed, the resource allocated by the master cannot work, so it remaps the resource to the new core ID slot.

static int

l2fwd_launch_one_lcore( attribute ((unused)) void *dummy)

{

unsigned lcore_id = rte_lcore_id();

if (float_proc) {

unsigned flcore_id;

/* Change it to floating process, also change it's lcore_id */

clear_cpu_affinity();

RTE_PER_LCORE(_lcore_id) = 0;

/* Get a lcore_id */

if (flib_assign_lcore_id() < 0 ) {

printf("flib_assign_lcore_id failed\n");

return -1;

}

flcore_id = rte_lcore_id();

/* Set mapping id, so master can return it after slave exited */

mapping_id[lcore_id] = flcore_id;

printf("Org lcore_id = %u, cur lcore_id = %u\n",lcore_id, flcore_id);

remapping_slave_resource(lcore_id, flcore_id);

}

l2fwd_main_loop();

/* return lcore_id before return */

if (float_proc) {

flib_free_lcore_id(rte_lcore_id());

mapping_id[lcore_id] = INVALID_MAPPING_ID;

}

return 0;

}