4. Malloc Library¶

The librte_malloc library provides an API to allocate any-sized memory.

The objective of this library is to provide malloc-like functions to allow allocation from hugepage memory and to facilitate application porting. The DPDK API Reference manual describes the available functions.

Typically, these kinds of allocations should not be done in data plane processing because they are slower than pool-based allocation and make use of locks within the allocation and free paths. However, they can be used in configuration code.

Refer to the rte_malloc() function description in the DPDK API Reference manual for more information.

4.1. Cookies¶

When CONFIG_RTE_MALLOC_DEBUG is enabled, the allocated memory contains overwrite protection fields to help identify buffer overflows.

4.2. Alignment and NUMA Constraints¶

The rte_malloc() takes an align argument that can be used to request a memory area that is aligned on a multiple of this value (which must be a power of two).

On systems with NUMA support, a call to the rte_malloc() function will return memory that has been allocated on the NUMA socket of the core which made the call. A set of APIs is also provided, to allow memory to be explicitly allocated on a NUMA socket directly, or by allocated on the NUMA socket where another core is located, in the case where the memory is to be used by a logical core other than on the one doing the memory allocation.

4.3. Use Cases¶

This library is needed by an application that requires malloc-like functions at initialization time, and does not require the physical address information for the individual memory blocks.

For allocating/freeing data at runtime, in the fast-path of an application, the memory pool library should be used instead.

If a block of memory with a known physical address is needed, e.g. for use by a hardware device, a memory zone should be used.

4.4. Internal Implementation¶

4.4.1. Data Structures¶

There are two data structure types used internally in the malloc library:

- struct malloc_heap - used to track free space on a per-socket basis

- struct malloc_elem - the basic element of allocation and free-space tracking inside the library.

4.4.1.1. Structure: malloc_heap¶

The malloc_heap structure is used in the library to manage free space on a per-socket basis. Internally in the library, there is one heap structure per NUMA node, which allows us to allocate memory to a thread based on the NUMA node on which this thread runs. While this does not guarantee that the memory will be used on that NUMA node, it is no worse than a scheme where the memory is always allocated on a fixed or random node.

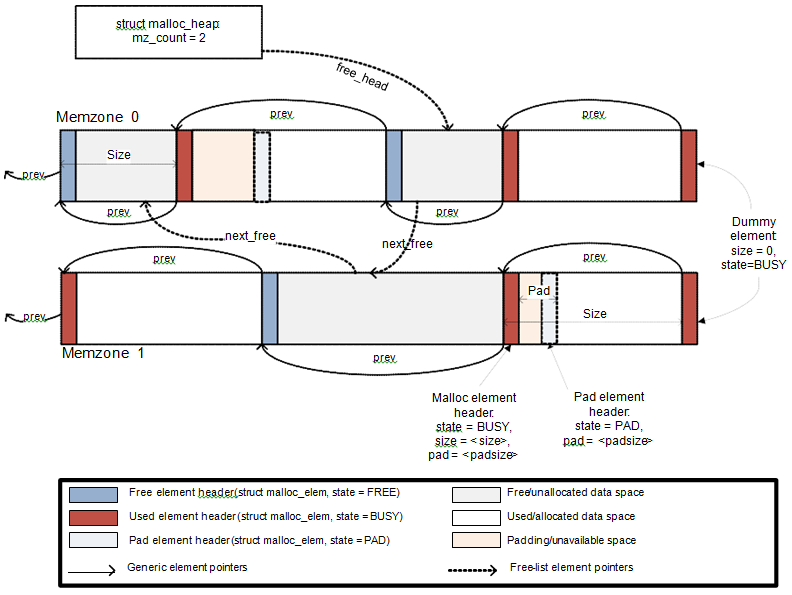

The key fields of the heap structure and their function are described below (see also diagram above):

- mz_count - field to count the number of memory zones which have been allocated for heap memory on this NUMA node. The sole use of this value is, in combination with the numa_socket value, to generate a suitable, unique name for each memory zone.

- lock - the lock field is needed to synchronize access to the heap. Given that the free space in the heap is tracked using a linked list, we need a lock to prevent two threads manipulating the list at the same time.

- free_head - this points to the first element in the list of free nodes for this malloc heap.

Note

The malloc_heap structure does not keep track of either the memzones allocated, since there is little point as they cannot be freed. Neither does it track the in-use blocks of memory, since these are never touched except when they are to be freed again - at which point the pointer to the block is an input to the free() function.

Figure 3. Example of a malloc heap and malloc elements within the malloc library

4.4.1.2. Structure: malloc_elem¶

The malloc_elem structure is used as a generic header structure for various blocks of memory in a memzone. It is used in three different ways - all shown in the diagram above:

- As a header on a block of free or allocated memory - normal case

- As a padding header inside a block of memory

- As an end-of-memzone marker

The most important fields in the structure and how they are used are described below.

Note

If the usage of a particular field in one of the above three usages is not described, the field can be assumed to have an undefined value in that situation, for example, for padding headers only the “state” and “pad” fields have valid values.

- heap - this pointer is a reference back to the heap structure from which this block was allocated. It is used for normal memory blocks when they are being freed, to add the newly-freed block to the heap’s free-list.

- prev - this pointer points to the header element/block in the memzone immediately behind the current one. When freeing a block, this pointer is used to reference the previous block to check if that block is also free. If so, then the two free blocks are merged to form a single larger block.

- next_free - this pointer is used to chain the free-list of unallocated memory blocks together. Again, it is only used in normal memory blocks - on malloc() to find a suitable free block to allocate, and on free() to add the newly freed element to the free-list.

- state - This field can have one of three values: “Free”, “Busy” or “Pad”. The former two, are to indicate the allocation state of a normal memory block, and the latter is to indicate that the element structure is a dummy structure at the end of the start-of-block padding (i.e. where the start of the data within a block is not at the start of the block itself, due to alignment constraints). In this case, the pad header is used to locate the actual malloc element header for the block. For the end-of-memzone structure, this is always a “busy” value, which ensures that no element, on being freed, searches beyond the end of the memzone for other blocks to merge with into a larger free area.

- pad - this holds the length of the padding present at the start of the block. In the case of a normal block header, it is added to the address of the end of the header to give the address of the start of the data area i.e. the value passed back to the application on a malloc. Within a dummy header inside the padding, this same value is stored, and is subtracted from the address of the dummy header to yield the address of the actual block header.

- size - the size of the data block, including the header itself. For end-of-memzone structures, this size is given as zero, though it is never actually checked. For normal blocks which are being freed, this size value is used in place of a “next” pointer to identify the location of the next block of memory (so that if it too is free, the two free blocks can be merged into one).

4.4.2. Memory Allocation¶

When an application makes a call to a malloc-like function, the malloc function will first index the lcore_config structure for the calling thread, and determine the NUMA node idea of that thread. That is used to index the array of malloc_heap structures, and the heap_alloc () function is called with that heap as parameter, along with the requested size, type and alignment parameters.

The heap_alloc() function will scan the free_list for the heap, and attempt to find a free block suitable for storing data of the requested size, with the requested alignment constraints. If no suitable block is found - for example, the first time malloc is called for a node, and the free-list is NULL - a new memzone is reserved and set up as heap elements. The setup involves placing a dummy structure at the end of the memzone to act as a sentinel to prevent accesses beyond the end (as the sentinel is marked as BUSY, the malloc library code will never attempt to reference it further), and a proper element header at the start of the memzone. This latter header identifies all space in the memzone, bar the sentinel value at the end, as a single free heap element, and it is then added to the free_list for the heap.

Once the new memzone has been set up, the scan of the free-list for the heap is redone, and on this occasion should find the newly created, suitable element as the size of memory reserved in the memzone is set to be at least the size of the requested data block plus the alignment - subject to a minimum size specified in the DPDK compile-time configuration.

When a suitable, free element has been identified, the pointer to be returned to the user is calculated, with the space to be provided to the user being at the end of the free block. The cache-line of memory immediately preceding this space is filled with a struct malloc_elem header: if the remaining space within the block is small e.g. <=128 bytes, then a pad header is used, and the remaining space is wasted. If, however, the remaining space is greater than this, then the single free element block is split into two, and a new, proper, malloc_elem header is put before the returned data space. [The advantage of allocating the memory from the end of the existing element is that in this case no adjustment of the free list needs to take place - the existing element on the free list just has its size pointer adjusted, and the following element has its “prev” pointer redirected to the newly created element].

4.4.3. Freeing Memory¶

To free an area of memory, the pointer to the start of the data area is passed to the free function. The size of the malloc_elem structure is subtracted from this pointer to get the element header for the block. If this header is of type “PAD” then the pad length is further subtracted from the pointer to get the proper element header for the entire block.

From this element header, we get pointers to the heap from which the block came – and to where it must be freed, as well as the pointer to the previous element, and, via the size field, we can calculate the pointer to the next element. These next and previous elements are then checked to see if they too are free, and if so, they are merged with the current elements. This means that we can never have two free memory blocks adjacent to one another, they are always merged into a single block.